Chavin De Huantar Plan Birth of Venusap Art History

Archaeological site of Chavín de Huántar (photo: Julio Martinich, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Art for the initiated

The artistic style seen in stone sculpture and architectural decoration at the temple site ofChavín de Huántar, in the Andean highlands of Peru, is deliberately complex, confusing, and esoteric. It is a mode of depicting non simply the spiritual beliefs of the religious cult at Chavín, but of keeping outsiders "out" while letting believers "in." Only those with a spiritual understanding would be able to decipher the artwork.

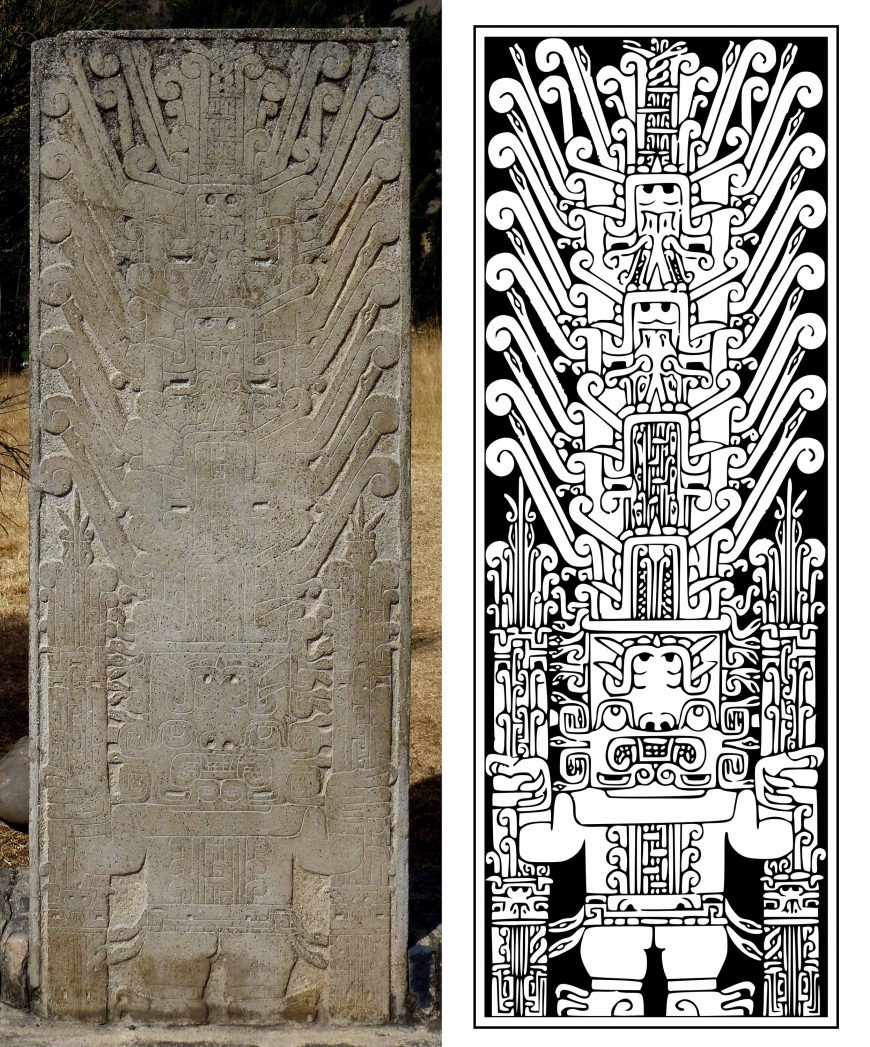

Left: the Raimondi Stele, c. 900-200 B.C.E., Chavín civilization, Peru (Museo Nacional de Arqueología Antropología e Historia del Republic of peru, photograph: Taco Witte, CC BY ii.0). Correct: Line cartoon of the Raimondi Stele (source: Tomato356, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Raimondi Stele from Chavín de Huántar is an important object considering it is so highly detailed and shows Chavín style at its most circuitous. It is easiest to see in a drawing, because the original sculpture is executed by cutting shallow but steep lines into the highly-polished rock surface, making information technology very difficult to make out the incised image. This style is deliberately challenging to sympathize, thereby communicating the mystery of the Staff God, and creating a difference between those initiated in the faith who can sympathise the imagery, and outsiders who cannot.

Powerful animals

The stele (see video directly below) shows the god holding staffs composed of numerous curling forms. Beneath the god's easily nosotros encounter upside-down and sideways faces, and the staffs terminate at the peak in ii snake heads with protruding tongues. The god'southward belt is a compressed, bathetic confront with two snakes extending from where the ears should be, perhaps substituting the snakes for pilus, and turning the face with its snake-hair into a belt. The god's easily and feet have talons rather than human fingernails, evoking felines and birds of prey.

These are references to animals that would have been exotic rumors to the people of highland Chavín: the jaguar, the harpy eagle, and the anaconda are all animals that dwell in the lush tropical jungle over the Andes mountains to the east. They are all noon predators, possessing concrete qualities like strength, flight, and stealth that become metaphors for the ability of the Staff God. Other supernatural imagery from Chavín includes images of caimans, crocodile-similar animals that also inhabit the eastern jungles. Most people would never have seen these creatures, rendering them mythical in their own right, and suitable for depicting the mysterious nature of the god.

Multiple faces

The god'southward face is really equanimous of multiple faces (see video directly below). The optics in the center looking upwardly are above a downturned oral cavity sporting feline fangs, only below that we can see some other upside-downwards pair of eyes and a nose that use the same mouth. This is an artistic technique known as contour rivalry, where parts of an image tin be visually interpreted in multiple ways. A similar thing is taking identify on the god's "forehead," where we see another upside-down rima oris with four large fangs protruding from it, which when associated with the eyes in the middle completes a full face. In a higher place this multi-faced head is what appears to exist an enormous headdress, which is composed of more faces that besides multiply using contour rivalry, and have extensions emanating from them that terminate in curls and snake heads.

An intricate style

This intricate and confusing style was not just used for large monuments at Chavín. Smaller carved, decorative elements of the site's architecture likewise display these kinds of supernatural figures. The 2 stone slabs seen below are examples of the kinds of sculptures found in cornices and other architectural elements at Chavín.

Stone sculpture (Museo Nacional de Chavín, photo and drawing: Dr. Sarahh Scher, CC By-NC 4.0)

1 of these depicts a standing effigy with snakes for hair. It sports the same protruding fangs we meet in the upside-downward heads above the Staff God's face. Large pendant earrings rest on its shoulders, and in its hands it holds ii shells: a Strombus in its correct manus and a Spondylus in its left. Spondylus shells are not native to Republic of peru; they thrive in the warm coastal waters of what is now Ecuador, hundreds of kilometers from Chavín. Early on in the history of the Andes, there was a brisk trade in these shells as luxury items.

Carved Strombus shell trumpet (pututu) (Museo Nacional de Chavín, photo: Dr. Sarahh Scher, CC BY-NC iv.0)

Strombus can be found in Peruvian waters, only that is the southernmost achieve of their range—they are more common in the north. A nifty number of carved Strombus shells turned into trumpets (called pututu ) have been found at Chavín. Far from the ocean, these shells symbolized water and fertility. Furthermore, the Strombus is oftentimes associated with masculinity, while the Spondylus has feminine associations. The two together therefore signaled generative fertility and the ability of the cult to foster agricultural prosperity.

Cornice sculpture (Museo Nacional de Chavín, photo and drawing: Dr. Sarahh Scher, CC Past-NC 4.0)

A 2d carved figure is more than enigmatic, and is full of contour rivalry . The primary effigy appears to be composed of the caput to the right, attached to a body with circular spots, probably alluding to a jaguar. However, backside the head is another center, olfactory organ, and fanged mouth, and the jaguar spots are joined by an middle with a contour rima oris with fangs. Thus, what appears to be one creature at first glance may be every bit many every bit iii. At the lesser left, we can run across another fanged mouth, this i upside-downwards, only considering the stone is broken, nosotros've lost its context.

The spread of the Staff God

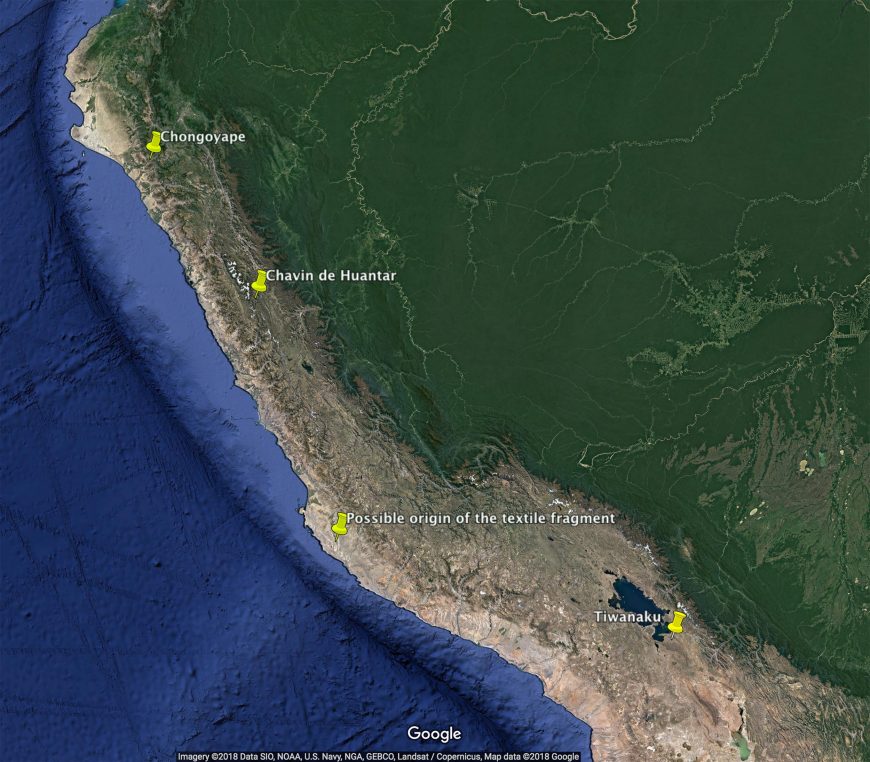

The image of the Staff God would spread throughout Peru. The imagery'southward geographic accomplish gives us some insight into the contact between distant areas and the diffusion of imagery. Once idea to show the expansion of the cult of Chavín, today scholars are more hesitant to draw direct relationships between Chavín influence and these far-flung images. The Staff God may have had its roots in before cultural styles, including the one known as Cupisnique, making Chavín just one of many expressions of this deity. The Staff God'south imagery traveled extensively, far beyond the areas already mentioned.

Cupisnique-manner crown, 800-500 B.C.Due east., golden, 24 × 15.5 cm (National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Establishment, photograph: Dr. Sarahh Scher, CC BY-NC 4.0)

A Cupisnique aureate crown from Chongoyape, Peru, besides demonstrates the Staff God'south attain. The crown depicts a version of the god that is simpler than that seen in the Raimondi Stele, but it still uses contour rivalry and the trademark fanged mouths.

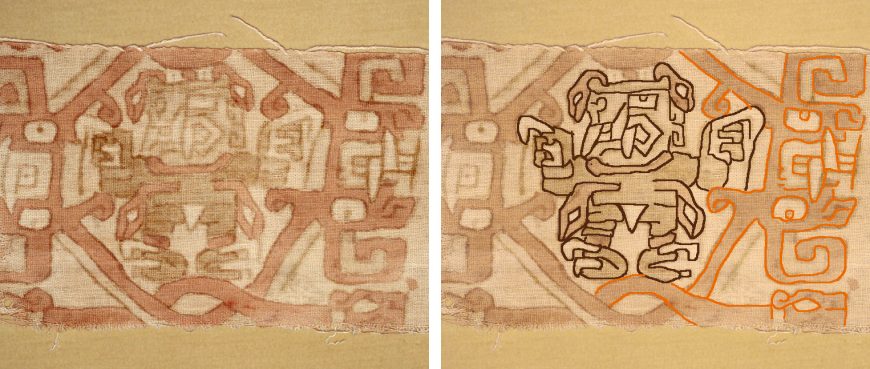

Material fragment, quaternary–3rd century B.C.East., Chavín culture, Republic of peru, cotton, refined fe earth pigments, 14.6 x 31.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, cartoon by Dr. Sarahh Scher, CC BY-NC 4.0)

A painted textile fragment with the Staff God is idea to be from the southern Peruvian declension, hundreds of kilometers from Chavín (which is in the highlands). It is woven from cotton, which is a coastal agricultural product, and distinct from the camelid wool that came from the highlands. The Staff God here is shown with the head in profile, and with snakes emerging from the peak of the caput, with a feline-fanged mouth, serpent belt, and taloned easily and feet. The figure is enclosed in a knot-like shape, equanimous of supernatural figures that blend ophidian and feline attributes. Other southern coastal textiles with Staff God imagery have been plant, including some that render the Staff God every bit explicitly female, showing how this religious imagery transformed as it traveled.

Map of Peru showing the locations of objects with Staff God imagery (© 2018 Google)

Traveling in fourth dimension

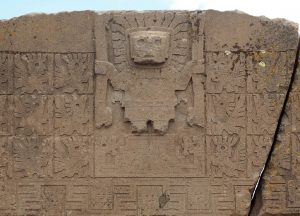

The image of a divine figure holding staffs or similar objects in its hands would persist in Andean art long past the time of Chavín. The so-called "Sun Gate" at the site of Tiwanaku, most lake Titicaca in modernistic-24-hour interval Bolivia, is 748 miles (most 1200 km) from Chavín. It dates from around 800–1000 C.E., and then is separated by at least a grand years from the Raimondi Stele. However, like the Stele, it features an abstracted and intricate way that separates believers from outsiders.

Sun Gate, Tiwanaku, Bolivia (photo: Brent Barrett, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Sun Gate, Tiwanaku, Bolivia (photo: Ian Carvell, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Tiwanaku manner is more angular than Chavín, and the Sun Gate has a strong gridded organization that adds to the geometric feel. The central figure of the Sun Gate, while sharing the frontality of the Staff God and the familiar pose (artillery at the sides, elbows aptitude, and vertical objects in its grasp), is too dissimilar from earlier iterations. The head is unduly big, rendered in a higher relief than the rest of the effigy, and features projecting shapes that may represent the rays of the lord's day. Some terminate in feline heads in profile, a change from the earlier serpents seen at Chavín, Chongoyape, and in the textile fragment. In its easily it holds projectiles and a spear-thrower—weapons rather than elaborate staffs.

The Sunday Gate effigy stands atop a stepped pyramid shape with serpentine figures emerging from it, a representation of the Akapana pyramid, which mirrored the nearby sacred mount Illimani not only in shape but by having a series of internal and external channels that allowed rain water to cascade down the side of the construction like the higher up-and below-footing rivers of the mountain. Not only does information technology stand in the aforementioned pose every bit the Staff God; it, too, is associated with natural forces, similar the mount, the sunday, and the waters of Illimani. The feline heads terminating the rays from the effigy'south caput are joined by the bird-human hybrid "attendant" figures in the rows to either side.

The meaning of the Staff God image was likely different in each of the places it has been establish, an image of the sacred that came from distant and was adopted and adapted to the needs of the local people. In each case, withal, we find that the intricate and often inscrutable imagery was a way of keeping believers separate from outsiders.

Boosted resource:

Richard L. Burger, Chavin and the origins of Andean civilization (London: Thames and Hudson, 1995).

Julia T. Burtenshaw-Zumstein, Cupisnique, Tembladera, Chongoyape, Chavín? A Typology of Ceramic Styles from Formative Flow Northern Peru, 1800-200 BC, doctoral dissertation, University of E Anglia, 2014.

Joanne Pillsbury, Timothy Potts, and Kim Northward. Richter, Gold Kingdoms: Luxury arts in the ancient Americas (Los Angeles: Getty Trust Publications, 2017).

Recordings of pututus

Source: https://smarthistory.org/the-staff-god-at-chavin-de-huantar-and-beyond/

0 Response to "Chavin De Huantar Plan Birth of Venusap Art History"

Post a Comment